Normal distribution (source: wikipedia.org)

Normal distribution (source: wikipedia.org)

Just about everything in your life is an event with some probability for a particular outcome. There are not almost any things that are certain.

Sounds crazy? Consider that even what we ordinarily take as certain in the physical reality around us is not really certain in the probabilistic sense. It may be close to 100% probability but according to modern physics nothing is 100% certain.

For example, we cannot even have 100% certainty that a book dropped from the table will fall on the floor. There is an extremely small chance that it will levitate, fly up instead of down or fall down but in a different way than predicted by classical theories (or something else entirely will happen). This chance is so small we can treat it as 0 for practical purposes, but nevertheless, it is expressed in terms of probability because, at least philosophically, it's not an absolute certainty.

Given that even law of physics do not offer guarantees but probabilities, we clearly cannot claim anything close to certainty on events that hinge on social contract (“I'll meet you at 8pm at the pub”) or complicated (multivariate) physical systems such as weather.

We intuitively understand this and don't depend on the weather forecast “to a T”, rather, we treat it as a rough guideline with significant deviations expected (the further out in the future, the larger the deviation). Similarly, we usually may make very detailed plans for a few days ahead (down to an hour or even minute) but don't plan a year ahead with that level of detail. We may have a rough expectation of what our life is going to be a year or two out, but we usually don't make a detailed plan for a day that's a year from now because there is too much uncertainty with such an extended timeframe (we don't know if we're going to be alive, much less what we're up to, then).

However, even if we accept the premise of nothing being 100% certain, it doesn't of course mean that we completely give up any control and leave everything to chance. Our actions and behaviors can (and do) take advantage of the probabilistic nature of the world. We often unconsciously create probability functions for various events, such as getting to work on time (“Will I be late if I leave 30 mins early?") or asking a girl out on a date (“Will she say yes?"). Not that we often even vocalize the numbers or put them in a table somewhere, but based on some previous experiences and current signals we may internally make predictions such as: “Most of the days I should get to work on time” or “She likes me and we talked before and she doesn't have a boyfriend so there is quite a chance she'll agree”. If things change later on (commute starts taking longer due to road works or that girl now has a boyfriend - cruel, I know!), we can update the probabilities.

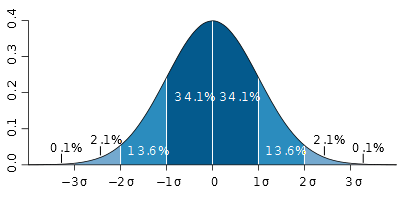

Similarly, most other events in our everyday life have outcomes that lie somewhere along a probability distribution too. The bus may be exactly on time but there is a non-zero chance that it will actually be either early or late. All possible times of the bus's arrival define a probability function. If success of a particular event depends on multiple other events all those probability functions will combine to create a joint probability function over all those outcomes.

Let's work through an example. Imagine your going to a concert (this is our “event” in the probabilistic sense). Say, a success of this event depends on only 5 other mutually independent events all being successful (which I'd say is a very conservative number, in reality it may be higher, this is to simplify calculations) and all of them have a quite high 80% chance of success:

- You wake up earlier than usual so you can come to work early and leave earlier than usual too

- You get to work on time (no traffic jams, public transport works, natural elements don't get in the way)

- Your boss approves you leaving work early that day and there are no unexpected urgent requests from management that you need to complete on that day

- Your trip back home is on time

- Your spouse is home on time too, to take care of the kids

The probability of all those 5 events being successful is thus 0.8 * 0.8 * 0.8 * 0.8 * 0.8 = 0.32 or only 32%! If we crank up the chance of success of each of those events to 90% that total is just barely above 50/50, at 59%! To be reasonably sure (let's say 95% sure) that we'll get there on time, we need all those events to be individually at 99% of success.

One of the ways you can increase the chance of success of the final event is to leave enough safety margin around the prerequisite events so that they don't crash your brittle plan so easily (that is, if you have any control over them at all). For example instead of expecting to get home from work in the usual 30 mins (without any allowance for travel delays), set aside 45 minutes, so that this event's success is expanded from a very narrow band of 25-30 mins to 25-45 mins and now covers a much wider range of possible outcomes.

Why write a blog post about it? For one. I think we tend to underestimate how multiplying even quite high individual probabilities can quickly result in a low combined probability, if there are enough chained events. The second reason is that it's worth reminding ourselves that we have control over outcomes that we care about and we can exercise this control.

One of the lessons from the calculation above is that leaving ample margins around your estimates helps increase the chances of success at the cost of spending more time “idling” (though such time can be creatively used for other purposes, I'm sure) and occasionally not allocating your money most optimally.

What is called “time management” is a really important weapon in the battle for success. Don't procrastinate and don't leave things incomplete until the very last moment. Conditions may change and you will not be able to finish them later due to other priorities, etc. An early start means you will have time to find any unexpected obstacles, redefine the task, ask for help, find additional resources, dig deeper, learn more about the subject, etc.

If you pick work up at the very last moment, you have basically gotten rid of any margins and, if anything goes wrong, you will not be able to finish on time. That's not called success, that's called failure and we'd like to avoid it if we can, right?

Money-wise you can set aside more than actually necessary for your purchases. Market prices are subject to frequent fluctuations and may change without much notice. Don't leave for your favorite restaurant with just enough money to pay for the meal. Take a bit more in case the price has gone up or you meet a friend who you'd like to get a drink for. You wouldn't like to be in a situation where you've arrived and found out the price has gone up by a dollar which you don't have on you.

On a larger scale, have more money saved in the bank than what you strictly need for current expenses. Without extra spare money you may miss out on some great bargains or be vulnerable to rapid changes in economy. This advice doesn't really bear any costs for regular folks with their spending money, but it may be a concern for businesses which can incur “opportunity costs” when not allocating their money in more optimal ways. Given this, this advice doesn't apply to businesses.

Redundancy is also a concept that we can apply here, usually at additional cost. Have spares or extras in case you lose the primary object. For example, when going for vacation, take an extra credit card in case your primary one gets lost. If you're going to give a presentation on your laptop, have a backup of it on a USB key in case your laptop dies on you - you can use somebody else's laptop to present from in such event.

Redundancy may be extended beyond physical object, to things like work skills. If you only have a single professional skill in life and want to achieve professional success, you're in a quite vulnerable position. What if your job gets obsolete or the only employer leaves town? It's good to invest in self-development to, again, increase your chances of success should your job situation unexpectedly change. Having more career options leaves you less vulnerable to such turmoils.

There is no 100% certainty in our lives but we can adjust our behaviors to increase chances of success. Hopefully the techniques listed above are just reminders of well-known folk wisdom that all of us apply everyday.

PS. On a personal note, I was recently on a 4-week holiday abroad that, due to external factors, had to be extended by another 2 weeks. If I hadn't had extra cash sitting in my bank account, this would be very bad news. Fortunately, this just meant I had to call work and tell them I won't be coming for another 2 weeks and then I enjoyed extra time off. Boy, was I glad I had some “rainy day” money like this! It offered me a great peace of mind and reinforced the ideas on managing uncertainty offered in this post. It kind of spurred me to write this post as well.