Formulas are a succinct way of encapsulating an insight into a symbolic expression. However, I've been treating some of them purely for their computational utility, without understanding the underlying insight. I'd plug in the numbers, run the arithmetic within and out would come the result, Sure, that's one powerful functionality that formulas offer but they also contain the crux of the insight that somebody once had and put into the formula. Occasionally I would even consciously realize that I have no idea why certain expression looks that way it does but I still wouldn't stop and try to understand it, which is quite a self-limiting behavior.

In this short post I'd like to share a few examples of where I've missed the insight as it was obscured by the symbols but fortunately eventually came to a more fundamental understanding. This should leave me with some hope that in at least some cases this is not an impossible feat, but rather my reluctance to dig deeper and glossing over the formulas has left me with suboptimal understanding or even entirely without any understanding. Those examples are rather basic and some would laugh at my lack of understanding of really quite basic stuff. I appreciate that but feel like full disclosure is the best way to go about it.

One of the chronologically first confusing expressions for me were units of acceleration. Introduced to me I'd guess sometime in my early teens a curious unit of:

\[\frac{m}{s^2}\]

was quite counter-intuitive. No teacher has explained (or more likely I might have missed it) to me what seconds squared are supposed to represent. Can you raise time to the second power and if so, what is the result of such operation? What is the intuition behind it? Those questions are legitimate but I didn't have the answers. Turns out this unit starts to make sense in a possibly less compact but equivalent and much more intuitive representation of:

\[\frac{\frac{m}{s}}{s}\]

Now it's clear that the units in the numerator are meters per second (velocity) over seconds (time) in the denominator, that is, they show how much velocity (in \(\frac{m}{s}\)) you gain or lose per second, which is acceleration! Suddenly it makes sense and now it's even easy to answer such questions as “At what velocity is an object moving in 5 seconds after having been dropped from a tall tower?". Knowing that Earth's gravity is around \(10\frac{m}{s^2}\), for each second of the fall you add \(10\frac{m}{s}\) of velocity, so after 5 seconds the velocity should be around \(50\frac{m}{s}\)! Easy peasy!

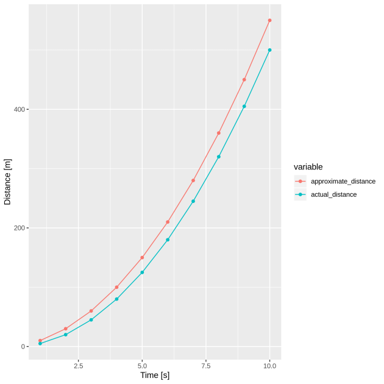

This method is not very exact for calculating the distance the object has traveled but the approximation might be good enough for some purposes. We know that in the first second of its fall the object might have only traveled at maximum 10m (as its velocity at the end of that first second has only just reached 10m/s). Similarly at the second second it might have traveled at most 20m, the third second at most 30m, etc. We know we're overshooting but possibly not by a whole lot. When we graph this approximate result vs the actual distance, we're off by only 10% after 10s have passed (our estimate is 550m vs the actual 500m):

Confusing units show up all the time in physics. I'm not really into physics but even looking at a list of derived SI units it's easy to notice a multitude of expressions with dimensions raised to second, third or even fourth power. For example watts have dimensions of \(\frac{kg \cdot m^2}{s^3}\). Now that we're armed with the understanding of the dimensions of acceleration, it should be possible to decompose the dimensions of watt (power or rate of energy flow): \(\frac{energy}{time}\). So we know that the denominator must be in seconds and the numerator should be \(\frac{kg \cdot m^2}{s^2}\) and the whole unit expands to: \(\frac{\frac{kg \cdot m^2}{s^2}}{s}\). Now we're dealing only with seconds squared (not cubed anymore) and we have seen those before! They were one of the symbols in the acceleration. Is that a coincidence? Not at all, since acceleration is indeed involved. It turns out that \(\frac{kg \cdot m^2}{s^2}\) is the same as \(\frac{kg \cdot m}{s^2} \cdot m\) which in turn is \(N \cdot m\) and N (newton) is mass times acceleration, which expands to \(\frac{m}{s^2} \cdot kg\), and we already know the left hand side of this expression is acceleration.

Unfortunately, most of formulas in mathematics and physics as well as physical units are presented in their final, most condensed and reduced form. It does take work to interpret them as something more meaningful that will hopefully illuminate the hidden insight. An additional benefit is that this process of decomposition and interpretation should leave a lasting and memorable impression of the formula in our mind. And what's more, if we do discover the hidden insight, we might never need to remember the formula again as we will be able to derive it from scratch when we need it.

Another example is counting k-permutations of n. In other words, we have a set of n elements and want to count in how many ways we can permute (arrange) any k of them. The formula is not very cryptic:

\[\frac{n!}{(n-k)!}\]

but even in its limited complexity it manages to hide a simple insight.

Looking at a formula presented like this, you're just tempted to plug in the values of n and k and get the result. In fact, this closed-form formula is a slightly opaque representation of a concept of falling factorial, which has its own symbolic representation of \(n^{\underline{k}}\) (also called a Pochhammer symbol). Falling factorial is a factorial that doesn't need to go all the way from n to 1, like \(n\cdot(n-1)\cdot(n-2)\cdot \ldots \cdot2\cdot1\), but instead only goes from \(n\) to \((n-k+1)\): \(n\cdot(n-1)\cdot(n-2)\cdot \ldots \cdot(n-k+1)\). For example \(10^{\underline{3}} = 10 \cdot 9 \cdot 8\). So the denominator in the closed-form formula is just there to get rid of the unneeded portion of the full factorial in the numerator (in other words divide by 7!):

\[

\require{cancel}

\frac{10 \cdot 9 \cdot 8 {\cancel{\cdot 7}} {\cancel{\cdot 6}}

{\cancel{\cdot 5}} {\cancel{\cdot 4}} {\cancel{\cdot 3}}

{\cancel{\cdot 2}} {\cancel{\cdot 1}}}{ {\cancel{7}}

{\cancel{\cdot 6}} {\cancel{\cdot 5}} {\cancel{\cdot 4}}

{\cancel{\cdot 3}} {\cancel{\cdot 2}} {\cancel{\cdot 1}}}

\]

The multiplication in the denominator doesn't come from a deep principle but rather only serves an arithmetic utility, so that no new symbols (like Pochhammer symbol) need to be introduced.

The real insight of the formula is that using the multiplication principle, you can select say 3-permutations of 10 elements in \(10 \cdot 9 \cdot 8\) ways and the closed-form formula is just a convenient expression that allows you to plug in the numbers and get the result.

The above formula for k-permutations of n comes up in the formula for the number of combinations, the so-called “n choose k” formula:

\[\frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}\]

Again, for me that not an intuitive formula at all. The way I prefer to think about it and memorize it is that we can permute k elements out of n-set in \(n^{\underline{k}}\) ways (the falling factorial I mentioned above) but each distinct set of k elements appears k! times (because each of its permutations is counted) so we need to divide that number by k! to get the final formula:

\[\frac{n^{\underline{k}}}{k!}\]

which in my opinion doesn't obscure the insight anymore, but rather exposes it. Wikipedia article on binomial coefficients mentions “this formula is easiest to understand for the combinatorial interpretation of binomial coefficients”