Euclid holding a compass in a painting of about 1474 (courtesy of Wikipedia)

Euclid holding a compass in a painting of about 1474 (courtesy of Wikipedia)

One of the earliest known examples of an algorithm is a 2,300+ years old algorithm by Euclid to find the greatest common divisor (GCD) of two integers. It is a very well studied algorithm, a true classic in the field of mathematics and computer science, but I only understood how it works and the intuition behind it very recently.

Well, better late than never, and so that you, dear reader, are spared such ignorance, I will try and present a hopefully intuitive reasoning on why it works.

There are many expositions of this algorithm out there already (not the least of those is by Donald Knuth in the opening chapter of his magnum opus “The Art of Computer Programming”), but hopefully mine also can add a bit of clarity to those who, like me, prefer a more graphical approach.

It is a very short algorithm, i.e. the number of steps is tiny, there are not many branches, etc, and you could just memorise it, but I wanted to understand the intuition behind it. As most commonly presented the algorithm operates on numbers but I only understood it after I switched to the domain of line segments (where it also works, once we constrain the domain), so I will present it with line segments.

The algorithm tells us to take two line segments (to expose the algorithm in its entirety, let them be of different lengths) which, by hypothesis, have a common divisor, or a common line segment that divides both without remainder (that stipulates that the lengths of these line segments must be either rational numbers or irrational but commensurable numbers, so it doesn't work on line segments of any arbitrary lengths). That is, there exists a line segment of a certain length which is contained an integral number of times in both line segments.

To find the GCD of a and b, Euclid's algorithm performs the following steps:

- Divide a by b, with quotient p and remainder c

- If c is 0, then the answer is b and the algorithm terminates.

- Replace a with b and b with c and go back to step 1.

The algorithm keeps doing those replacements and divisions until the remainder of the division is 0. The divisor in this division is the answer.

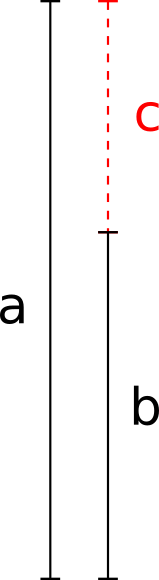

I had difficulty grasping why in step #3 we can replace the initial division \(a \div b\) with \(b \div c\). What does one have to do with another and why does it make sense? Turns out that representing this algorithm graphically helped me understand it so I want to share it with you. Here is the initial situation:

We have segment a, segment b and the remainder c (c < b). Why in step #3 can we replace a with b and b with c?

Euclid's great observation (or whoever came up with this algorithm, as it is suspected that Euclid only documented an already existing algorithm and didn't invent it) was that if a and b have a common divisor, then b and c MUST have that same common divisor too!

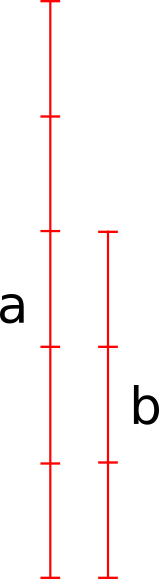

Let's try and reason about it. By hypothesis, we know that there exist some common divisor of a and b (even if it's just a “unit” length, or 1), let's call it g. Let's assume that it is NOT a divisor of c. Then, a is divisible by g an integral number of times (i.e. without remainder) and so is b. But if b is divided by g an integral number of times, let's say x, then it means if we “stack” g on itself x number of times, we get a line segment of length b, i.e. it's not shorter or longer, but exactly b. But we also know that if we stack g y number of times on itself, then we get a line segment of length a (it is a divisor of a too). Here is this situation shown graphically:

Therefore, g must be contained in c exactly \((y-x)\) number (an integral number) of times! It is a contradiction to our assumption that it is not a divisor of c! And since it cannot be a divisor and not-a-divisor (two contradictory things) at the same time, we conclude that it is a divisor of c.

This is the crucial insight that allows us to reduce the problem to smaller numbers and keep going in the same fashion until the remainder of the division is 0 and the algorithm terminates.